Yesterday when I realized I hadn’t posted the Miata Magazine Blast from the Past, I looked through the first magazine of 2000 I found just the article I would use because I actually attended that event with other members of the Masters Miata Club. But I hadn’t written about it on the blog previously, so I dug up my old Club newsletter from that time and published it yesterday,

Jacks or Better

MCA Poker Run a Resounding Success

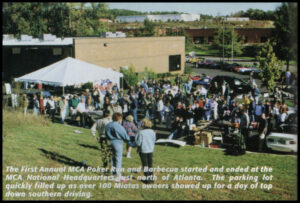

On a sunny fall Saturday, the national office of the Miata Club of America held its largest and most successful event thus far. Beginning at their offices north of Atlanta, Georgia, over 100 Miatas and their owners invaded the parking lot and offices this past October 23, 1999. The hardy souls braved the blustery and chilly weather for a great day of top-down Miata fun.

Groups from the Peachtree, CAMS, Florida Panhandle, Masters, and Foothills chapters joined local enthusiasts for a fun-filled day. Old friends from as far away as Ohio and Michigan made the long trip. An adventurous couple from New York used the event as an excuse for a road trip in their new 10AE. The couple drove down to enjoy a weekend in Atlanta.

Groups from the Peachtree, CAMS, Florida Panhandle, Masters, and Foothills chapters joined local enthusiasts for a fun-filled day. Old friends from as far away as Ohio and Michigan made the long trip. An adventurous couple from New York used the event as an excuse for a road trip in their new 10AE. The couple drove down to enjoy a weekend in Atlanta.

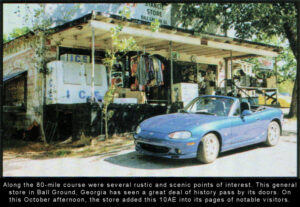

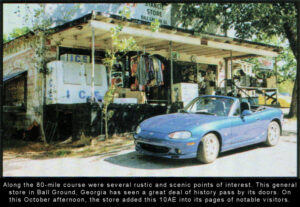

The afternoon began with a leisurely 80-mile drive through the colorful north Georgia countryside. MCA President, Vince Tidwell, did the honors of manning the starting line. Miata owners were seen motoring by horse farms, browsing at country stores, shopping for mountain property and admiring the sailboats on a nearby lake. The hungry travelers were welcomed back to headquarters with plenty of food including barbecue sandwiches, coleslaw, baked beans, and the now famous “Miata Club” cookies. Those who chose not to drive had ample time to shop and converse with the aftermarket vendors in attendance – including R-Speed, Autocentric, Top Notch Accessories, and Liberty Mutual Insurance.

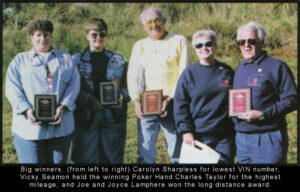

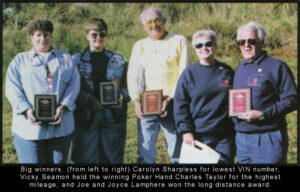

After all had driven, eaten and shopped until they were satisfied, it was time for the awards and prizes. Awards were given for the highest poker hand – a straight flush from Sonny and Vickie Seamon of CAMS, and the second highest poker hand – three of a kind from Eric and April Holtzclaw of Acworth, GA. In addition, plaques were awarded to honor the following: Furthest distance traveled, presented to Joe and Joyce Lamphere, from Vestal, New York. Charles Taylor of Conyers, GA easily won for the highest mileage with his Candy Apple Red ’90 Miata that showed over 364,000 miles on the odometer. The Lowest VIN number award was presented to Carolyn Sharpless of Austell, GA for her Miata built in April 1989. After the awards, a bounty of raffle prizes were given away. Everyone went home a winner as all participants were given a commemorative deck of Miata Club of America playing cards as a keepsake of the event.

After all had driven, eaten and shopped until they were satisfied, it was time for the awards and prizes. Awards were given for the highest poker hand – a straight flush from Sonny and Vickie Seamon of CAMS, and the second highest poker hand – three of a kind from Eric and April Holtzclaw of Acworth, GA. In addition, plaques were awarded to honor the following: Furthest distance traveled, presented to Joe and Joyce Lamphere, from Vestal, New York. Charles Taylor of Conyers, GA easily won for the highest mileage with his Candy Apple Red ’90 Miata that showed over 364,000 miles on the odometer. The Lowest VIN number award was presented to Carolyn Sharpless of Austell, GA for her Miata built in April 1989. After the awards, a bounty of raffle prizes were given away. Everyone went home a winner as all participants were given a commemorative deck of Miata Club of America playing cards as a keepsake of the event.

The Miata Club of America wishes to thank the Peachtree Miata club and all the hard-working volunteers who helped make this a successful event. They are a great bunch of people and were of invaluable service. The Poker Run would not have happened without this group of dedicated Miata owners.

The Miata Club of America wishes to thank the Peachtree Miata club and all the hard-working volunteers who helped make this a successful event. They are a great bunch of people and were of invaluable service. The Poker Run would not have happened without this group of dedicated Miata owners.

Keep watching Miata Magazine for future events, as at least two more are in the works for next year. Without a doubt, one of these events will be the Second Annual Poker Run and Barbecue.

Copyright 2000, Miata Magazine. Reprinted without permission.